Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES! Today’s guest needs no introduction. You know him from KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, THE WHITE DARKNESS, THE LOST CITY OF Z. That’s right, say hello to David Grann. We caught up a few weeks ago, ahead of the street date for his latest book, THE WAGER, which hits shelves Tuesday and will no doubt be lighting up the bestseller lists. (And not just because of last night’s glowing 60 Minutes segment.) I’m gonna shut up now so we can get right to it…

Tell me about THE WAGER.

It’s a crazy yarn about an 18th Century British naval warship called The Wager, and its crew, who are chasing a Spanish galleon filled with so much treasure it was known as the prize of all the oceans. But the ship ends up wrecking on a desolate island off the Chilean coast of Patagonia. They try to build an imperial outpost, but instead slowly descend into a real life Lord of the Flies, with waring factions and murders and mutiny. A few of the men succumbed to cannibalism.

Where’d you get the idea to do a book on this?

The genesis was this journal, The Narrative of the Honourable John Byron.

That’s Lord Byron's grandfather.

Yeah, grandfather of the poet. I was doing research on mutinies, which is like, one of my weird pet obsessions, and I came across this journal from the 18th Century. Its prose is very stilted. It's got this very archaic language. But as I was reading, I kept pausing, and almost being seized by certain descriptions. At first they had this unbelievably horrible outbreak of scurvy. Then he described the typhoon they battled trying to round Cape Horn. Then he described the shipwreck and this mutiny. And I realized that this unusual, odd little old account held the clues to one of the most fascinating sagas I had ever come across.

This would’ve been a few years ago when you started digging in?

I think it was late 2016. I went and did a little more research, and I discovered that many of the castaways had written their own journals or narratives of their accounts. And what really drew me to the story was that several of the castaways made it back to England, and after everything they've been through, they're suddenly summoned to face a court-martial for their alleged crimes on the island. After all that, they could be hanged. And so they release these accounts, hoping to sway the admiralty, and public opinion, to save their lives. It leads to this crazy war over the truth in which there are these competing narratives. There's disinformation, there's misinformation, there's even allegations of a kind of 18th Century version of fake news. It felt like a parable for our own turbulent time.

You had to acquaint yourself with all these different historical subjects—18th Century naval vessels, typhus, et cetera.

I really spent the first year just trying to learn the language, how ships were built, what life was like, reading books by British naval historians. I had some wonderful British naval historians who are world leading experts, and I'm sure they were very sick of me pestering them and asking for tutorials. I had to learn how to read these documents that were often written with shorthand or symbols. There are wonderful delights in this education, like learning about how these ships were built. It could take as many as 4,000 trees to build a single war ship. They were kind of engineering marvels of their time, and yet they were completely perishable because they were made of wood.

You also had access to an unbelievable trove of sources, including logbooks and diaries. How much of a lightning strike is it that so much firsthand material about a relatively obscure historical event from centuries ago was so well preserved?

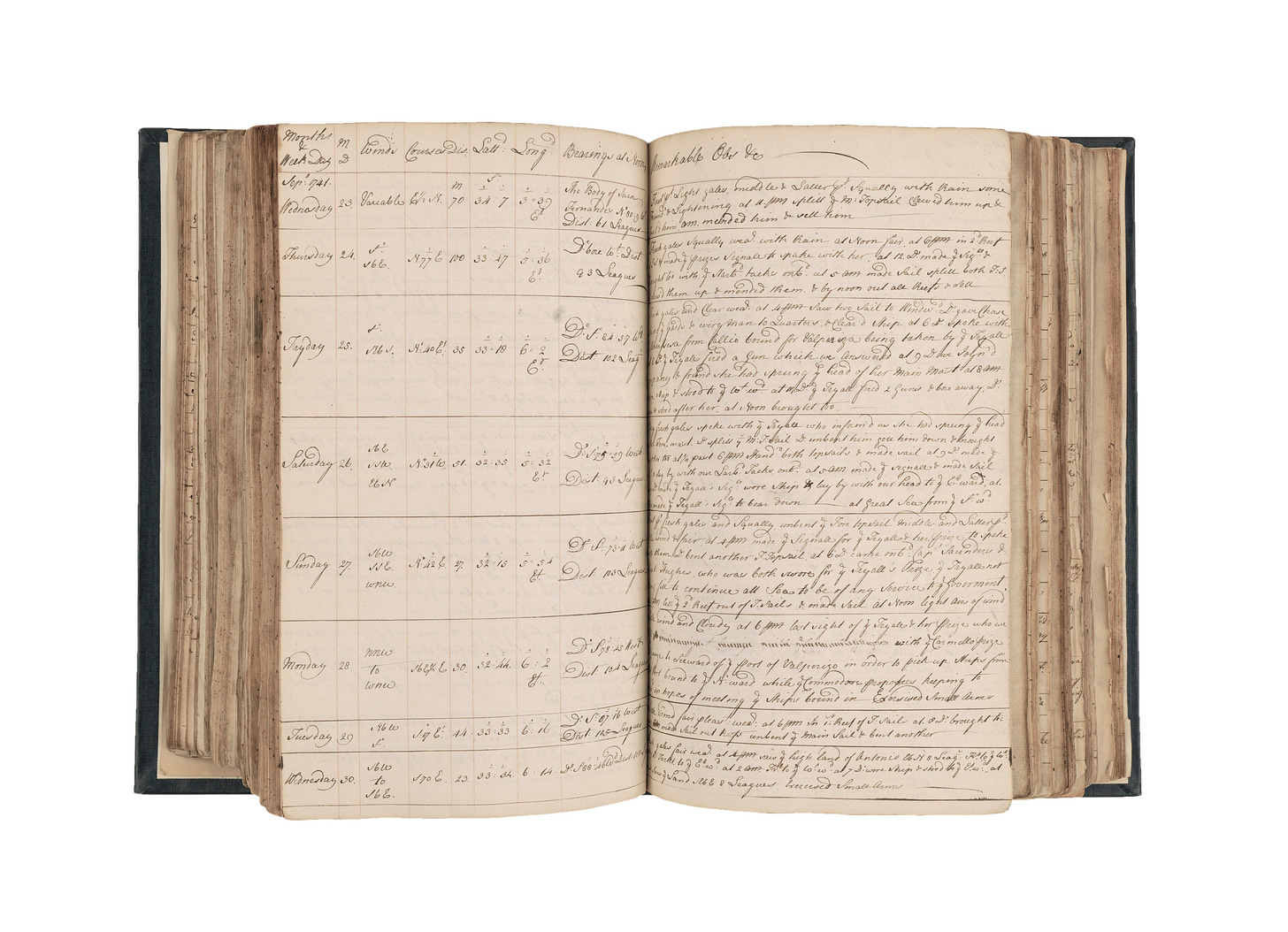

The British Empire, as part of its kind of malignant mission of imperialism, sought to document and keep records of distant realms that were being visited. And so seamen were required, in that age, to keep these logbooks, and they would be turned in after the voyage. It's stunning to go to the British Archives, to open up a box, to pull out a brittle logbook where, you know, basically you just blow on it and it turns to dust, and here's a book that went around the world.

When you found out that these logs existed, did you know they'd be as detailed and prolific as they were?

I didn’t. The other thing that happened in this case is, because some of the men were summoned to face court-martial, if they didn’t tell a convincing tale they might be hanged, and so they wrote these stories. So that’s another reason why there’s such a wealth of materials. These accounts were a sensation in their day, because it was scandalous what had transpired on that island. While now virtually forgotten, these accounts in their day were were studied and read by Voltaire, Rousseau, Herman Melville, Charles Darwin. And then of course Patrick O’Brian wrote a novel that was inspired, in part, by the Wager disaster.

What’s it like going through these records at the British National Archives? Like, physically.

You go in, and you put in a request for whatever documents you're looking for. Then they bring them out, usually in a box of some sort. There are all these strict rules that are in place, for good reason, on how to handle the documents, because some of these books are nearly three-hundred years old, so you really have to be careful in the way you touch them, even the way you open them so the bindings don't break apart. I would often use a magnifying glass to read them because the text is very small. I eventually hired a young man to help make digital images. It was just too expensive to keep flying back and forth.

How hard is it to decipher three-hundred-year-old handwriting?

You realize, as a historian, how much you are at the whims of the writer. There was a captain who was a very clear writer, very detailed, and I would always love when I would go through his logbook. But then you come across another officer's logbook and it's like, slanted and very abbreviated. It could be a challenge. I would often pester these naval historians if I had any questions about something.

There’s a scene in the book where Byron is climbing the main mast of the ship, and you really feel like you’re right there with him at every step.

What's great about that is you have Byron's account, but you also have so many seamen’s accounts of the climb of the mast. There was really one way. You all went up the same way. And there's lots of very vivid descriptions about how to do it. And again, to understand the technical language of how they did it, I remember consulting these British historians. So there's actually a really surprising amount of narrative description of what that was like, but even once I wrote it, I then went over it line by line, word for word, with two naval historians, just to make sure I got everything right.

Tell me about the three-week voyage you made as part of the research.

I really did not initially think about going to Wager Island. I spent the first two years just doing the research, and getting these documents and studying them, and reading a ton of books and trying to become fluent in this historical period, on what life was like on a ship, on the sociology of a ship. But there came a point where I began to fear that I would never really understand what it was like for the castaways on that island. I had never been to Patagonia, and I had certainly never been to Wager Island, this kind of desolate, windswept, barren island off the Chilean coast of Patagonia. And so I found a Chilean captain to take me there. He originally sent me some photographs, and the boat looked pretty big, but when I got there it was pretty small. I think it was about fifty feet, very top heavy, heated by a little wood stove.

Did you take one of those Dramamine injections?

When we started out, first we followed the channels around Patagonia, which are sheltered and very beautiful. You're kind of between all these little islands. And you think, ah, this is pretty good. And then, after several days, the captain's like, well, we gotta go out into the ocean now. That's when I got a glimpse of these seas, and I was like, you gotta be kidding me. That boat was just tossed about like a tin can. It was like being inside a ping pong ball. I had taken those things you put behind your ears, like there's some patch that you wear.

A scopolamine patch?

I think that's what it was. So I had that behind my ear. I had some band you wear on your wrist. I don't really think that did much of anything. And then I'd taken enough Dramamine to be like, half asleep. You just had to sit on the floor for hours and hours. To pass the time, I listened to Moby Dick on my phone. That probably wasn't the most soothing thing.

And this was the same time of year when the crew got stranded on the island?

It was right in the winter when they would've been there. It was rainy. I was all bundled up and I was still really cold. But it helped me understand what it must have been like for them, because they just had, you know, some fragments of clothing they had gotten off the ship, and much of their clothing disintegrated when they were on the island over time. And so I got a sense of how cold they were. I got a sense of how hard it was to walk across the island, because the land is either very mountainous or very boggy with dense foliage. It's like pushing through hedges. And I also couldn't really find any sources of food. There were no animals other than some birds. And then we found some of the kind of celery which they had eaten in their desperation. Going there was so important because it really helped me to understand why this British officer once described the island as a place in which the soul of man dies in him.

Were you able to track down living descendants of any of your characters?

There were a few, but they knew so very little. There was one who was helpful, gave me a couple letters, but it was just such long time ago. They knew of the story, but that was about it.

You knew more about the story than they did.

Yeah. One of the things that really drew me to THE WAGER was, after KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, I was so interested in why certain parts of history are told and burnished, and other parts are whitewashed and excised from our consciousness. And The Wager provided this perfect illustration of that. Not only did you have individuals each trying to shape and manipulate their own histories, you ultimately had the empire and those in authority saying, I don't know if we like any of these stories, and trying to kind of create their own mythic version of history. You can really see it play out in this case, so that was one of the reasons I really wanted to tell the story.

MORE SOURCE NOTES: