Elyse Graham on BOOK AND DAGGER

"A story about the librarians and scholars who invented modern spycraft."

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES. And say hello to Elyse Graham, a Stony Brook University professor whose latest work, BOOK AND DAGGER, was described by The New York Times Book Review as “a plea for a better understanding of the role played in espionage by the book, the imagined story, the artist, the writer, the humanities and the ‘library rats’ who study them.” Away we go…

What is BOOK AND DAGGER about?

The OSS, the precursor to the CIA, came together very quickly in the wake of Pearl Harbor. Lacking a standing spy agency, the U.S. needed to pull together a company of spies very quickly, and they decided to do so by recruiting the nation's professors and librarians. So this is a story about the librarians and scholars who invented modern spycraft. It's also a story that has a lot to teach us about today's world—for instance, it teaches us about the value of libraries, not just as centers of community and education, but as something that's integral to national security.

Did you become aware of that history through your work as an academic?

I've been writing about the history of universities for a while, and I became curious about why so many recruits to the CIA in the 1950s and 1960s were recruited out of departments of history and literature. It turns out that their professors had been spies during World War II, which seemed like a very interesting story, and it only got more interesting the deeper I got into it.

When did you first start digging?

Maybe around 2018, and the proposal was submitted in early 2022.

You did a fair amount of globe-trotting for this.

A lot of different libraries and archives. I remember while I was doing research at the British Library, the people manning the desk were young people who spent the whole time complaining to each other about the French, which I enjoyed very much. I went to Beaulieu, which is a little distance away from London—it's the site of a spy training school where the British Special Operations Executive used to prepare agents for undercover work. The students lived in beautiful country houses, and they had housemasters and servants and such; meanwhile, the Americans were training in muddy camps with canvas tents in national parks, where they were learning how to do quickdraws like cowboys.

Of course.

In England and elsewhere, professors were recruited to do code breaking, that sort of thing. And they were recruited to work the equivalent, in other countries, of the branch in the OSS that was called Research and Development—a very traditional sort of spy branch where scientists built bombs and designed poisons. You know, the stuff that Q does in James Bond. The Americans had one great innovation, which was this: they recruited professors from humanities fields like literature, history, economics, political science, anthropology. This was something new in the world of spycraft—and the type of spycraft these unlikely agents invented, intelligence analysis, became the basis of how we do intelligence today.

So the places you visited abroad were places where your characters had been.

Where they had been, where they trained, where they worked. I wanted to get a sense of what that world was like for them. I wanted to be able to understand the landscape and the local culture in a way that didn't come exclusively from reading books.

Gimme an example.

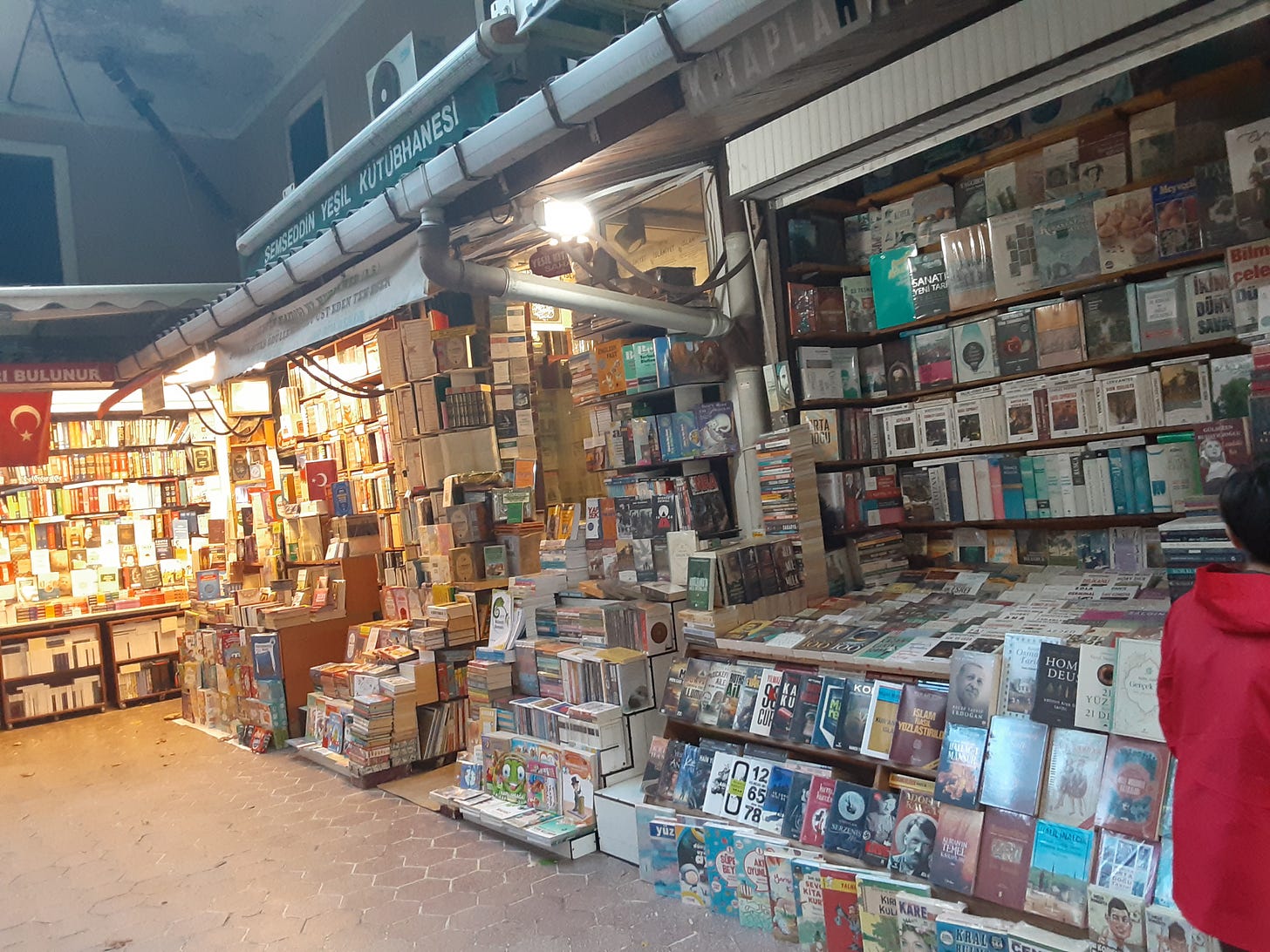

One of the characters, Joseph Curtiss, he spent quite a lot of time—because he was supposed to be abroad buying books for the Yale Library, that was his cover—in the Old Book Bazaar in Istanbul. I visited that place in person, and I was able to compare it to old references, archival photographs, that sort of thing. I got really into reading about the strategic theory of buying, selling, and negotiating in the bazaar, which has significant overlaps with the kind of information exchanges that you're involved in as a spy.

Tell me about the CIA files you obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

A lot of them had personal information about the agents, to the point of describing, like, one of them had—well, the agent was extremely racist, so I don't feel bad sharing with the world he had folliculitis of the buttocks. But in general, those files had information that the agency gathered before, during, and after their time as spies. Very, very personal information about specific people.

You also talked to former intelligence officers.

Some of those contacts came through Princeton, my alma mater, and that school in particular has close alumni ties. As an interviewer, you can't get somebody who works in intelligence to talk about everything. But if you're interested in the way that spies think, they will share that with you—and that's incredibly valuable information.

What other archives were particularly fruitful?

The National Archives were super helpful. Although I will note that, in the National Archives, the finding aids were made by OSS veterans, and they did heroic service, but they often made records of the names of men and not the names of women. So, you do have really wonderful records of women agents in the National Archives, but you can't find them using the usual finding aids. You have to get the help of archivists who know the terrain very well themselves.

The Yale University Library was also incredibly helpful. It has the papers of Sherman Kent, one of the characters in the book. He wrote a memoir that never got published, which is a shame because it's very entertaining. He was an interesting guy—as a professor, he used to throw chalk past the heads of his students when he thought they weren't paying attention to him. (They don't let us do that anymore.) Which is a nice character detail: it gives a sense of someone who's kind of restless—looking for a fight—before he enters the war, and it gives an indication of why he didn't return to Yale after the war. He liked fighting, and his new job in the CIA allowed him to do that.

Aside from the Sherman Kent memoir, what other unpublished material did you get your hands on?

Letters, of course, and records from the OSS, the SOE, and other such institutions. And I drew on a lot of wonderful secondary sources to combine those primary sources with things that had been published. But luckily there was no end to material in the archives that hadn't really been looked at. A war produces a lot of documentation.

You used two biographical researchers. What sort of work did they do?

I asked them to pull up information from the census, that sort of thing. Stuff that would've been very tedious to do on my own. They did terrific and heroic work. I was very grateful for it.

Right. The genealogical sort of stuff, because ancestry.com only gets you so far.

Exactly. And although I visited the National Archives in Maryland to do research in person, I hired a freelance researcher named Sim Smiley to find and photograph materials there, as well. The same job that one of the characters in the book, Adele Kibre, had before she entered the war. Smiley did absolutely incredible work—I highly recommend her.

I’d love to know how you navigated the handful of imagined scenes that you included for narrative continuity.

There are maybe four of those scenes in a four-hundred-page book—so, not an excessive number, I hope. But, for instance, we know that historically, Curtiss was asked to do wetwork. We don't know whether he did wetwork. So I wrote a scene that tried to think through how he might have thought through whether to do wetwork. It ends with him approaching his target—I don't say whether he winds up stabbing him or not, but I describe how he would have been trained to do it, which is to walk past him and then stick the knife up behind his back and into the other guy's back, into his kidneys, and then pull it out and keep walking so that nobody sees him do the actual stabbing.

Yikes.

I actually collected books from the period that included the spy training schools' fighting manuals. How you were taught to do close combat—to fold a newspaper, for instance, to turn it into a deadly weapon. Or how to stab somebody as you were walking past them. How to weaponize a makeup compact, if you were a woman. I bought a compact from the time period so I could figure out how to do that particular move. There’s a recruiting scene that's set inside one of the SOE offices—before I wrote it, I looked at historical pictures and blueprints of the building. In the book, I labeled each one very clearly as an imagined scene, but I wanted to make them as historically authentic as possible.

This is your first commercial book, right?

Yes.

How did the approach differ from your academic books?

One difference is that a book proposal for a commercial book is effectively a business proposal. You want to demonstrate that this book will sell, that it will be a good commercial product, and that isn't really something that book proposals for academic books have to consider. My proposal for this book wound up being about 85 pages long, whereas if you write a proposal for an academic book that's, say, 20 pages long, people will tell you to cut it in half.

Another difference is that a commercial book, if it's nonfiction, often includes other genres in addition to nonfiction. It's true crime, or it's historical romance, or, in my case, it's a spy thriller. A genre is a set of expectations on the part of the audience, so while you're writing, you have to think about the kinds of story elements, the kinds of details, that belong to the genre. As a historian, if you read enough, you have a potentially infinite number of details to choose from, so it’s a matter of selection. A lot of the best details actually come from very dry sources. You should always read the boring stuff, because that's where the interesting stuff is.

One thing that I had to my advantage was that the people building this spy agency didn't necessarily have spy experience themselves. So they used spy novels, spy movies, as their sources. They would tell someone they were recruiting, “Go to this place, you should wear a purple necktie, you'll see a man who will light a cigarette, then put it out. He's your contact.” They got that stuff from spy stories.

Now that you’ve done a work of popular history do you want to do more?

I'm working on a proposal right now. I can't tell you much, but it's about women committing crimes and having a marvelous time doing it. The research is a lot of fun. I enjoyed learning how to think like a spy, and now I'm learning how to think like a criminal.

Brilliant interview! lovely read-

Excellent interview! And just bought a copy. : )