Margalit Fox on THE TALENTED MRS. MANDELBAUM

“Her attire was at once gorgeous and vulgar. She often wore $40,000 worth of jewels at once.”

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES. Even if you’ve never read one of Margalit Fox’s books, chances are you’ve read one of the more than 1,400 obits she wrote for The New York Times. While I’m tempted to point newcomers in the direction of 2018’s magnificent CONAN DOYLE FOR THE DEFENSE, the subject at hand is Margalit’s new book, THE TALENTED MRS. MANDELBAUM: The Rise and Fall of an American Organized-Crime Boss, which hit shelves July 2. Let’s get into it so you have time to grab a copy before hitting the beach this weekend. (Speaking of which, I’m down the shore on vacation myself, so you won’t get my usual Friday roundup.)

Tell me about Mrs Mandelbaum.

When we hear the phrase “organized crime boss,” we think of either Tony Soprano or, if one is a certain age, Bruce Gordon playing Frank Nitti on THE UNTOUCHABLES. In other words, a big mean strapping guy—emphasis on guy—with spats and a Tommy gun in the middle of Prohibition. Lo and behold, it turns out that the first major organized crime boss not only predated the Prohibition guys by more than half a century, but wasn't a guy at all. She was a nice, zaftig Jewish mother-of-four named Fredericka Mandelbaum.

Is your book a biography?

A full biography will never be possible. For any writer of nonfiction, particularly historical nonfiction, one's first port of call is your subject's personal papers. Guess what? There were none, at least none that anyone has found. She was not stupid. She knew, in her line of work, that everything she did to make her capitalist fortune was illegal. It would be suicide to commit anything to paper. And so what I had to do was like a prospector panning for gold. I had to scour literally hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of written records, mostly historical newspaper articles, some in nice clean digitized copies, but many on microfilm that was itself so degraded, portions of the microfilm were black. There were also court records. When you're in her line of work, there's going to be court records. And, happily, in this era of contemporary indictments, we were able to find her original indictment papers from when she was finally arrested and brought to trial in 1884. There were also memoirs, interestingly, from her contemporaries on both sides of the law. A number of thieves wrote memoirs, and so did the police chief for much of her heyday, a man with the wonderful name of George Washington Walling. In the end, I was able to piece together a mosaic.

How did you find her?

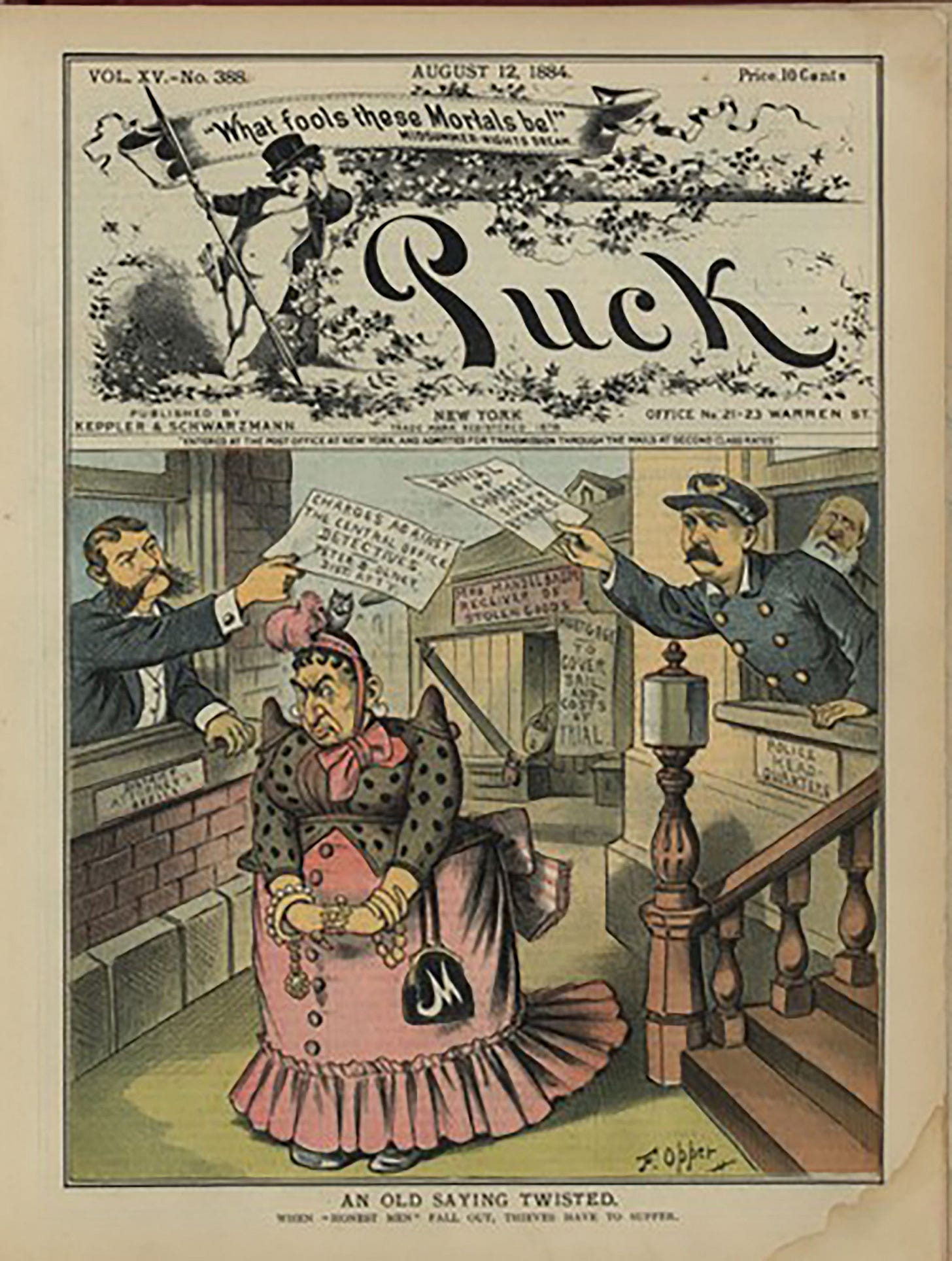

She was throwing off these little glimmering sparks just below the surface of history. It should be noted that, in her day, throughout the 1860s, seventies and eighties, she was literally world famous. She wasn't just covered in the New York papers, but papers from coast to coast. Her death in 1894 was covered as far away as London. She was the subject of editorial cartoons and there were even two stage plays in the late 19th Century that had characters transparently based on her. She was big news. But like so many people in women's history—and because she left no written records—she was largely forgotten. She has cameos in any number of books on New York history, particularly 19th Century crime. She makes a few cameos in Herbert Asbury's GANGS OF NEW YORK. She was always there, and it made me start to wonder, who was this woman? And how could she have done what she did?

So you'd come across her name in your travels.

Whenever I finish a new book, I cast about immediately for what to write next. In doing that, I usually turn to all sorts of arcane, interesting, long out of print volumes on the shelves of my personal library in my apartment in New York. One of the volumes I pulled down was a very very vast encyclopedia of crime. And serendipitously, it opened to a tantalizing entry. The entry said that in the 19th Century, there was an instructional academy where these aspiring young American Oliver Twists could go and be schooled in the arts of housebreaking and safe cracking and jewel robbery. I learned right away that it’s a totally spurious story—an urban legend. However, to my joy, the woman who was supposed to be the head of the school, Fredericka Mandelbaum, turned out to be very, very real.

You got some great material from the New York City Municipal Archives.

I got the whole indictment. I got all of these microfilm newspapers, many of which were not on databases like newspapers.com. My understanding is that some of their records go back to New York in the colonial days.

And you were researching during the height of Covid.

The entire book was reported during lockdown. So thanks to the combination of modern digital technologies and communications media and obliging staffs, I was able to do all of the research I needed to do from my home in New York.

Were you able to visit some of the physical locations where she operated?

The front for her illegitimate business was a quasi legitimate business, a haberdashery shop on the southwest corner of Clinton and Rivington streets on the Lower East Side. Her building, which was made out of wood, survived only into the early 20th Century. So the actual building is not there, but of course the neighborhood is there. There's a newer sort of sandstone building there now. I've certainly been down there. But I would be romanticizing things if I said there were still discernible traces of her after one hundred fifty years.

Which newspapers were the most fruitful?

The Times did a lot. The Herald. The Tribune. Every major city had many, many different English language daily papers. And this is one of the things that taught me right away how big she was. There's a wonderful quote that I think turns up early in my narrative where a newspaper says, rather with a combination of awe and disdain, “Her attire was at once gorgeous and vulgar. She often wore $40,000 worth of jewels at once.” That wasn't from a New York paper—that was from one of the Cincinnati papers. And when she was apprehended, indicted and brought to trial—or I should say, brought to the threat of a trial in 1884, all sorts of out-of-town papers covered her pretrial hearings. There's a wonderful description of how both she and her lawyer, the deliciously corrupt William Howe, who represented the entire New York underworld, how they each blazed into court covered in diamonds. That's from one of the Atlanta papers. That’s how big she was. She was national news.

You consulted three 19th Century academics to ensure accuracy.

Journalism is nothing if not enfranchised dilettantism. And we are always trespassing into territory that experts know much better than we. For every single one of my books, I hire a minimum of three scholars in that field to vet the manuscript. It's sort of a gut-churning moment when the Word doc comes back with all of the edits. It's like getting a test back from your teacher. But their stuff is invaluable, and it saves one from a lot of, as I say in the book, interloper’s idiocies.

The average reader probably doesn't realize the lengths authors go to in order to get even the smallest little details right. Like how you consulted a mathematician to understand what it takes to crack the combination of a safe.

I had read in some popular book on safe cracking that with a combination lock, a three-digit combination with no repetitions in the sequence has close to a million permutations. And that a four-digit one has close to a hundred million. It sounded right to me, but my degrees are in linguistics. I'm not a mathematician. And so I asked a friend who is a mathematician. I sent him a PDF of just that one page and he responded back immediately saying, yes, these are correct.

There are so many great books about crime in this period. Which ones helped ground you in telling Mrs. Mandelbaum’s story?

Of course Herbert Asbury, which has to be taken cum grano salis, was a good point of entree. Tyler Anbinder’s book about the Five Points was very helpful. If you look at the very, very, very long bibliography, there are sources that range from as early as the 1850s to historians writing up to the present time.

And now, you’re already busy researching your next project

Yes. It's also historical true crime, narrative nonfiction, about the Somerton Man case. It's a very interesting true crime story. And very different from this one.