Matthew Goodman on PARIS UNDERCOVER

"I'm the first person in seventy five years who has discovered this."

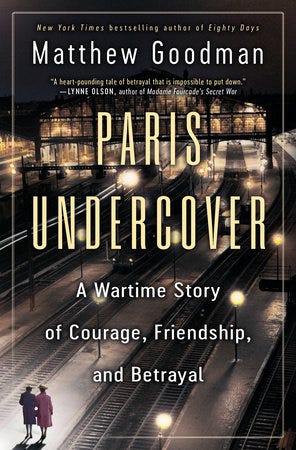

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES. And give a hearty welcome to Matthew Goodman, decorated author of page-turners on Nellie Bly and the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, whose latest book, PARIS UNDERCOVER: A Wartime Story of Courage, Friendship, and Betrayal, is out this month from Ballantine. “Goodman’s gripping account … illustrates how loyalty and betrayal can coincide in wartime and its aftermath,” raves The Washington Post. But don’t just take their word for it. Here’s Matthew…

Tell us about PARIS UNDERCOVER.

It’s the true story of Etta Shiber and Kate Bonnefous, two older women in Paris in 1940—an American woman and an English woman separated from her French husband—living entirely conventional lives. When the Nazis occupy Paris, the women end up creating an escape line that transports dozens of allied servicemen, both English and French, out of occupied France and to freedom. And then—

I know that’s not the whole story of the book but it sounds like it could be the whole story.

Well when I proposed the book, that was the book. I should backtrack and say that their escape line was in operation for three months, at which point it was infiltrated by the Gestapo. When they were arrested Etta, the American, she was given a lighter sentence because America was not yet in the war. She was sentenced to three years in a Nazi prison. And Kate was sentenced to death. Etta, after eighteen months, is traded in a prisoner swap and returns to the United States in 1942, at which point she's approached by a publisher who wants her to write a book.

The book comes out in 1943, titled PARIS UNDERGROUND, describing her activities with this escape line. It becomes a runaway hit—a bestseller on The New York Times list for eighteen weeks. It ended up selling half a million copies. It was excerpted in Reader's Digest. It became the basis of a Hollywood movie. And it made Etta a celebrity. What I discovered, in the course of working on my book, was that much of what is described in Etta’s memoir simply did not happen. It was fictionalized by the publisher for various reasons, but mainly having to do with wanting to sell more books, by making the exploits greater than they actually were in real life.

And you're the first author or historian to reveal this?

I'm the first person in seventy five years who has discovered this. Every story that I've read about Etta takes her book at face value, as I did when I first proposed this book, as an adventure story of these two women who get involved in doing something that was unlikely for them to do. I was intrigued by the notion of these two older women who were not glamorous, young, beautiful spies, but just kind of ordinary people who, when the time came, found it within themselves to resist authoritarianism. Once I started doing the actual historical research and trying to line everything up, there were details that I simply couldn't find. And little by little it became clear to me that a good portion of the book had been fictionalized. The book that I thought I was going to depend on as the primary source of my research turned out to be entirely unreliable.

Did you think about calling it a day?

I did think I was gonna have to return my advance to the publisher.

But instead this turned into a different sort of project.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the fictionalization of the memoir, how it had been fictionalized and why it had been fictionalized, was actually part and parcel of the whole.

That story required deeper digging, which was complicated by Covid.

I began my research just before the pandemic. The New York Public Library closed for a year. Plus, I couldn't get on a plane to go to England or France where a lot of the materials were. So for the first time in any of my books, I utilized a team of researchers.

How do you find them?

Mainly by people recommending them to me. For instance, my editor recommended the woman who became my primary researcher in Paris. So I had several in France, I had several in Italy, I had several in England. Probably ten overall. It got expensive. But they were enormously helpful. The French archives in particular are really byzantine, very hard to navigate.

Not everything was tucked away in some French or British archive.

Eventually I was able to trace who had actually written the book. It was a somewhat obscure Hungarian Jewish refugee, and I ultimately tracked that down in the Scribner's publishing archives, which are held at Princeton University. I tracked down his legal affidavit, because he sued to get credit and he stated in great detail that he had written the book, and that he had intended for it to be a novel, and he was shocked when he discovered it was going to be released as a memoir with the claim that all of the incidents depicted in the book were true.

And this was just sitting there in the Princeton archives all these years?

Yes. That was one of the last pieces of research I did. And that was the moment when all the pieces kind of clicked into place

It's amazing it was just a car ride away in central New Jersey. What other archives did you draw on in the U.S. besides Princeton?

The major one is the National Archives and Records Administration, just outside of Washington. That was extremely valuable because they had all the records of the American Embassy in Paris, and a lot of the work of this escape line was being done through this embassy. They had all the records of the State Department. This prisoner swap that Etta was involved in was negotiated via the State Department, so that proved to be extremely useful.

What sort of stuff did your researchers find in Europe?

I'll just give you a few examples. In the National Archives in London, there are hundreds of escaped prisoner testimonies that have been opened to the public somewhat recently, and they're a valuable source of information because they let you know which prisoners had been through Kate and Etta's apartment, and what their route was, and how the escape actually transpired. There's also a folder for Kate Bonnefous—who was herself interviewed upon her release from German prisons—in which she described at some length what her experiences in the German prison camps were. In France, there were corresponding folders, like those of all of the helpers, all the people who helped along the way, who the French government gave medals to, or paid restitution money to, and so forth. Those were also extremely valuable.

How did you track down descendants of Etta and Kate?

I had a genealogist in England who managed to track down descendants of the servicemen who had gone through their apartments. But then, through some genealogical site I was using, maybe Ancestry.com, I tracked down Etta’s grand niece, and Kate's two grandsons, one of whom lives in France and one of whom lives in Portugal. The one in Portugal is the guy that, like, every researcher wants to find, the keeper of the family record. He was the one who had all of Kate's stuff. He had saved it all.

What sort of stuff?

Well, for instance, her address book from that period, which had all of her sources. The newspaper clippings she had saved. Letters she had written and received. Doctors' reports, medical reports. Her own handwritten notes that she had taken. It was really a wealth of material. He told me, by the way, that he’d once had toilet paper that she had secretly written on while she was in this German prison, because it was the only writing paper that she had, but he couldn't find it anymore. So that was heartbreaking.

What about Etta?

Her grand niece gave me copies of a trove of letters she had written from Paris to her brother in Syracuse in the months immediately proceeding, and then immediately following, the German occupation. The letters before the war were full of details of their normal daily life—the meals that they ate, the movies they went to see, the names of their three Cocker Spaniels and where they walked 'em, where they went shopping. You know, all of that. And in the letters from after the German occupation, that was the key moment when I read her very detailed description of what happened when they fled Paris, and where they went, and how long they were gone for and when they returned. That’s when it became clear to me that what had been described in the memoir could not have happened.

That must have been a really exciting moment, but also the moment where you wondered if your book was falling apart before your eyes.

Exactly. It was definitely a moment of danger, but also I think I sensed it was a moment of opportunity.

For your next book, how are you gonna top having uncovered this major historical fraud?

You tell me! I don't know how it is for you, but for me, finding the next book topic is always the worst part.

Do you have one yet?

I don't. There are a lot of dry wells you have to get through before you find the gusher.