New revelations in the Hall-Mills murder mystery

An excerpt from BLOOD & INK's expanded paperback

To celebrate today’s release of the expanded paperback edition of BLOOD & INK, here’s a (lightly tweaked) excerpt from the postscript I’ve added to the book, describing an unexpected research breakthrough in the Hall-Mills murder case. It’s a story about how new information, even from a century-old mystery, can turn up in places where you’d least expect it.

“Hall-Mills jackpot enroute to NBFPL.”

That was the subject line of an email I received last winter from Kim Adams, archivist of the New Brunswick Free Public Library, whose name you will see again in my “Note on Research and Sources,” first published in the hardcover edition of Blood & Ink. It was February 8, 2023, and Kim had just gotten a call from a woman in upstate New York with a trove of papers related to the case. Would the library be interested in adding these documents to its Hall-Mills collection? Absolutely, Kim told the donor, quivering with excitement. Then she sent me an email: the papers in question, she explained, once belonged to Timothy Pfeiffer, the personal attorney, spokesman, and all-around loyal consigliere to Frances Hall, the accused husband-slayer from the four-year saga at the heart of this book. “These are coming to us,” Kim wrote, “and hopefully will provide you with some new and toothsome info.” My mouth watered at those words, but I had no idea just how new and toothsome Pfeiffer’s archive would prove to be.

After Blood & Ink first hit shelves on September 13, 2022, almost exactly one-hundred years to the day that Edward Hall and Eleanor Mills were murdered, I heard from numerous people with familial or personal connections to the story. [MORE ON THAT IN THE FULL POSTSCRIPT]

In the absence of a definitive conclusion, these interactions added nuance to my understanding of the case. On a more frivolous level, each new sliver of information felt like a thrill. But as I would soon learn, the biggest thrill of all awaited me more than three-hundred miles from home, in a tiny village along the Allegheny River .

“DEAR JOE,” KIM ADAMS WROTE a few weeks after her earlier email. “Just to help with your planning, Bob”—as in NBFPL director Bob Belvin—“will be going to New York State to pick up the materials at the end of April. There are about 8 boxes”—eight boxes!—“and, if I understand correctly, several albums of newspapers.”

As it turned out, I wouldn’t be able to wait until the end of April—my editor told me the deadline for updating the paperback edition was sooner than that. I asked Kim if she could introduce me to the donor of the Pfeiffer papers, which is how I ended up on the phone with Ronda Pollock late one afternoon in early March. She was at her second home in Clearwater, Florida, where she spends her winters. The good news was that, in another few days, Ronda would be flying back to her primary residence in Portville, the remote hamlet where Pfeiffer’s Hall-Mills collection had been gathering dust for the past fifty-two years. The even better news was that Ronda was happy to give me access to the records before turning them over to Bob Belvin and the library. She also insisted on hosting me in her beautiful storybook home, the same one that had been owned, once upon a time, by—you guessed it—Timothy Pfeiffer.

Over the phone, Ronda explained how Pfeiffer’s papers ended up in her possession. In 1969, she and her husband, Tom, decided to move back to their hometown after a decade in Florida. Pfeiffer had put the Portville house up for sale the previous year, after the death of his wife, Eleanor Knox Wheeler. The two-and-a-half-story Stick-style Victorian had been built in 1880 by Eleanor’s parents, whose wealth derived from a family lumber business. Pfeiffer and Eleanor, primarily based in New York City, used it as their summer retreat—a bucolic country idyll to which Pfeiffer escaped on weekends via the Erie Railroad. Portville became a second home to Pfeiffer, who amassed acres of open land and built a woodland cabin made of chestnut. Now that his wife was gone, it was time to entrust his beloved country home to new owners, the type who could be counted upon to honor its legacy. He found such stewards in the Pollocks, who agreed to buy the property after touring it a couple of times. “I think he was afraid that the house would either be torn down or made into apartments,” Ronda told me. “He didn’t want that to happen.”

The first time Pfeiffer showed the Pollocks around, he gestured to a large trunk in the corner of what was then the woodshed (now the eat-in kitchen). He said it contained all of his records from an old murder case back in the 1920s. “I should take everything in that trunk and burn it,” he remarked more than once.

Luckily Pfeiffer didn’t do that. Instead, he left the records with the house, along with stacks of old books and various pieces of furniture and other miscellaneous effects. The Pollocks stayed in touch with Pfeiffer until his death in 1971 in Princeton, where Pfeiffer had relocated in old age. They got to know his daughters over the years. Ronda, whose husband died in 2021, is still friendly with one of Pfeiffer’s grandchildren, Nicholas Vaczek, who joined us from Ithaca when I made my pilgrimage to Portville about a week and a half after that initial phone call.

On a chilly Sunday night, we sat in Pfeiffer’s former parlor—which to this day looks like something out of a late-nineteenth-century novel—enjoying a pre-dinner cheese plate and a bottle of red wine. It was not lost on me that Frances had almost certainly spent time in this very spot, at least if I was to trust the local lore indicating she had been a visitor to Portville. (I would find corroboration for this in Pfeiffer’s archive.)

As we drained our glasses, Nick said he’d discovered Blood & Ink through a piece I wrote for The New Yorker. Ronda had read it after seeing a review in the Wall Street Journal. She’d noted with interest the passage in my source notes where I describe Kim Adams’s earlier discovery of another long-lost trove of Hall-Mills records, acquired by the New Brunswick Public Library in 2019. Ronda had always wanted to do something with the Pfeiffer papers, now sitting in the nearby headquarters of the Portville Historical and Preservation Society, which the Pollocks founded in 1975. At one point she’d written to Princeton University, Pfeiffer’s alma mater, but never heard back. In a most auspicious turn of events, my book gave her the idea to send the papers back home, as it were, to New Brunswick.

As for Nick, he told me he’d spent a lot of time with Pfeiffer during childhood summers in Portville. He recalled Pfeiffer’s affection toward his grandchildren, his love of the opera, his home in Riverdale and small apartment on East Seventy-fourth Street, his days on the short-lived Harvard Law School football team. The one thing Nick couldn’t speak to was whether Pfeiffer harbored any secrets about the murder case that made his name. “It wasn’t a topic of family conversation,” Nick told me apologetically. “It wasn’t something we talked about.”

THE FOLLOWING MORNING, Ronda took me up the road to a quaint little schoolhouse dating back to 1864. It belongs to the historical society, and this was where Ronda had transferred the Pfeiffer papers several years earlier. Ronda pointed to the eight 12 × 15 × 10-inch cardboard bankers boxes, each packed to the brim with precious documents. Before we carried them over to a large table in the front of the room, she showed me a robust stack of bound newspaper volumes, including the original three New York tabloids whose origins are chronicled in Blood & Ink. During my earlier research, the one tabloid not accessible to me was Bernarr Macfadden’s Evening Graphic, because the microfilm at the New York Public Library doesn’t include any issues between 1924 and 1928. Now I held in my hands original copies of the Graphic dating back to the 1926 investigation, quite possibly the only physical collection of its kind: MRS. HALL ARRESTED! COLLAPSES IN CELL; PIG WOMAN’S BABY NEW HALL MYSTERY; MILLS ON GRILL CHANGES STORY; WIDOW BEGS KILLER TO CONFESS.

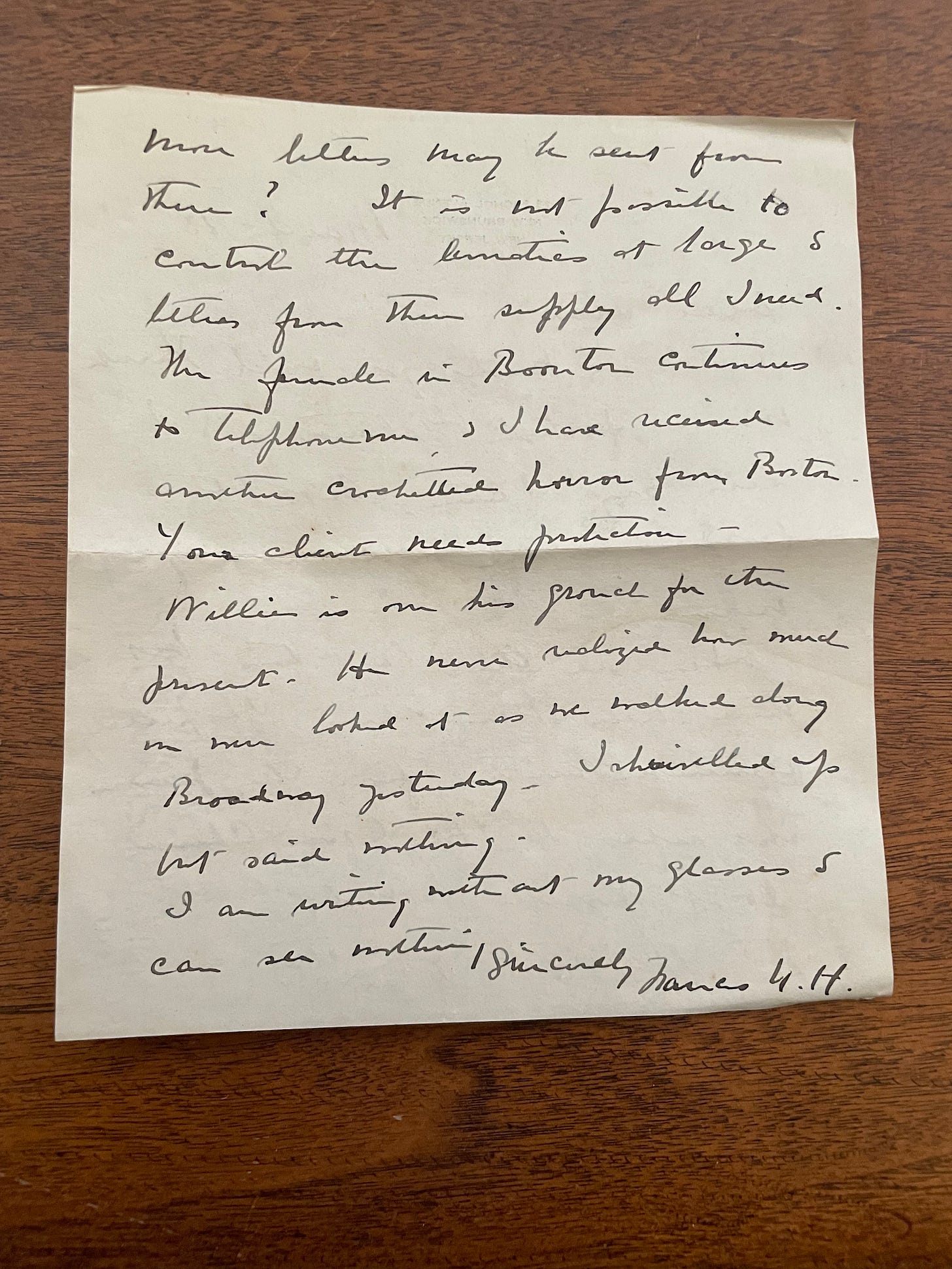

I could’ve spent hours with this tabloid treasure, but the bankers boxes beckoned. Over the next two days, I made my way through as much of the collection as I could. Papers in folders. Papers in envelopes. Papers bound together with rusty old paper clips on the verge of disintegration. Postcards, letters, newspaper clippings, sepia-toned photographs from more than a century ago. Handwritten and typewritten correspondence from Frances Hall. Jailhouse letters from her brother Willie Stevens. Day-by-day detective notes. Legal documents from the family’s libel suit against the New York Daily Mirror. Drafts of statements to the newspapers and memos outlining press strategy. Folders labeled with the names of pretty much every single character from the case, including characters I’d never even heard of.

To give you a sense of just how deep the rabbit hole went, I found an original print of the photograph that appears at the top of the cover of this book, the one with the five guys looking down at a spot near the crime scene. [SEE IMAGE AT THE BEGINNING OF THIS POST] The digital Getty Images file contains virtually no information about the photo’s provenance. But thanks to Pfeiffer’s exhaustive recordkeeping, I can report that it was taken by a photographer named Carl Francis on the afternoon of September 16, 1922, shortly after the bodies were found, and that the names of the men were “left to right—standing: Benj. Elfant, Louis Ruck, a taxi-driver, and the third is unknown. Schwarz, a prize-fighter promoter. Stooping—William Bauries.”

My time in Portville—where I also gave a talk at the historical society, visited the historic Pfeiffer-Wheeler American Chestnut Cabin, and paid my respects at Pfeiffer’s final resting place—was all too short. It would probably have taken a week or two to conquer the full collection; I managed to devote maybe ten or twelve hours to it. Back at the house on my second night, as I sifted through a couple of boxes that Ronda let me abscond with from the schoolhouse, I wondered what Pfeiffer would think of me sitting there in his beloved former summer home, inspecting the very documents he’d once considered burning. Would he applaud my efforts? Or was he rolling over in his grave less than a mile away?

In the end, before bidding farewell to Ronda and setting off on the long ride back to New Jersey, I was able to scan several hundred pages—out of thousands overall. If there’s a smoking gun hidden somewhere in those boxes, which are now in the possession of the New Brunswick Free Public Library, I haven’t found it yet. As for whether I’ve unearthed any intriguing clues, I’ll let you be the judge.

»If you’re a Hall-Mills completist and want to find out what I discovered in the Pfeiffer archive, click here to buy the paperback. (On that note, if you haven’t already dug into BLOOD & INK and find yourself wanting to know more, click here to buy the paperback. 😂) I hope you enjoy it. And thanks as always for reading.

Praise for Blood & Ink

“Blood & Ink is an addictive whodunit and a vivid depiction of a crime that gripped a generation of newspaper readers.”

—The New York Times Book Review (Editors’ Choice and Best True Crime of 2022)

“Pompeo retells the whole sordid business with care and authority, deftly pacing its astonishing developments. . . . Blood & Ink is among 2022’s best works of true crime.”

—Washington Post

“Engrossing. . . . Pompeo’s book is as much about the rise of tabloid journalism and the American public’s appetite for lurid true-life tales as it is about the crime itself.”

—Wall Street Journal

“A compulsively readable account of a sensational unsolved double murder a century ago. . . . Pompeo provides the definitive account of the murders. This is essential reading for true crime buffs.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A deliciously tawdry, well-told tale. . . . [Pompeo’s] research is exhaustive, his command of details complete, the narrative fast paced and captivating. . . . The result is first-rate historical true crime.”

—Washington Independent Review of Books

“A compelling narrative filled with page-turning suspense.”

—Ken Auletta, bestselling author and The New Yorker staff writer

“Excellent new book.”

—David Grann, bestselling author of The Wager and Killers of the Flower Moon

“Joe Pompeo vividly brings to life all of the color, drama, and in- trigue of a century-old murder case that continues to baffle investi- gators to this day. Set against the backdrop of a form of journalism that would metastasize in the decades that followed, Blood & Ink is a deft piece of investigative reporting and storytelling that refuses to lose its grip on the reader.”

—Bryan Burrough, bestselling coauthor of Barbarians at the Gate and Forget the Alamo

“Pompeo brilliantly presents one of the most fascinating cases in the annals of true crime, the Hall-Mills murders. Pompeo inves- tigates a story that fuses religion, betrayal, greed, and adoration, which offers us a complex and tragic portrait of a love story that seemed almost doomed from start.”

—Kate Winkler Dawson, author of American Sherlock: Murder, Forensics, and the Birth of American CSI

“Pompeo expertly tells the rip-roaring tale of a century-old murder and the ongoing mysteries surrounding the deaths of a minister and his choir-singer lover. Pompeo also shows how the rise of the New York City tabloids kept the scandal alive from one generation to the next. I couldn’t put it down. You won’t be able to either.”

—William D. Cohan, bestselling author of House of Cards