Paul Fischer on THE MAN WHO INVENTED MOTION PICTURES

"Thomas Edison wasn't going around murdering people."

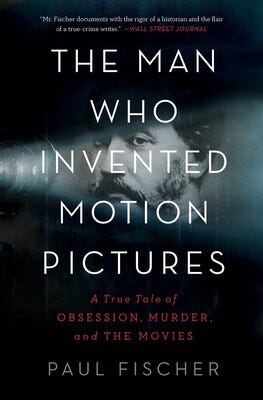

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES! Today I bring you Paul Fischer, author of THE MAN WHO INVENTED MOTION PICTURES: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies. It’s about the relatively obscure early-motion picture pioneer Louis Le Prince, his disappearance in Dijon, France in 1890, his race-against-the-clock rivalry with Thomas Edison, and the ongoing mysteries surrounding his presumed murder. THE MAN WHO INVENTED MOTION PICTURES came onto my radar last December, when Fischer’s book and mine had the privilege of sharing space on The New York Times Book Review’s year-end roundup of “The Best True Crime of 2022.” I finally read it this summer and asked Fischer for an interview as soon as I was done…

How did you come to this story?

There's a novel by Theodore Roszak, who’s a film academic, called FLICKER. I read FLICKER on holiday years and years ago. It's one of those six-hundred-page conspiracy thrillers, about this idea that cinema is invented by the Illuminati or something, and everything in film is subliminal mind control. He does this thing in the book, like THE DA VINCI CODE, where he mixes real-life stuff, real film history, with invented stuff. There was one big chunk of exposition in the novel where someone talks about this guy called Louis Le Prince, who supposedly made the first film and had the first patent and was killed on a train.

And you’d never heard of him, even as someone who works in film?

Who works in film, who grew up in France. I was fascinated by that era and I had never heard of the guy. So I Googled it, and yeah—he did make the oldest motion picture. It is only a few surviving seconds, but it exists. And the patents are in several countries, and the camera and a projector still exist in a museum somewhere. And he did disappear off of a train, and somehow I'd never heard of him.

As is often the case with these sorts of things, you stumbled upon a kernel of an idea in some other book you were reading.

That was the starting point.

When was this?

It was around 2010, 2011.

How long did you work on your book?

The proposal took a year on and off, and then once Simon & Schuster bought the book, it was three and a half years.

Your research spanned two continents and several countries.

He was French, but he worked in Leeds in the north of England, and then also worked a little bit in New York, but then sailed back and worked in Leeds for a few more years, but financially everything was tied up in France. The book is two stories. It’s him trying to invent this thing, and it's also the true crime aspect: what happened? For that, I wanted to dig into his family, which was in France, and I wanted to dig into Thomas Edison, because Le Prince’s family was convinced he had something to do with it. I would go to England, and I went to France, and then I went to New York and went out to New Jersey. And then I had researchers spending more time in each of those locations.

I live about a ten-minute drive from the Thomas Edison National Historical Park. What did you find there that was useful in telling this story, which Edison is a big part of?

Not that much, except walking around and getting a feel for the geography. They digitized a whole bunch of papers for Rutgers, and that was a lot more useful. Edison had this guy called W.K.L. Dickson, who invented motion picture devices for him, one of his engineers. So, in-person at the Edison site was more a case of, okay, if I'm writing about W.K.L. Dickson in the photography room, that's where it is, that's what that looks like. The thing about Edison is, he's a big hook because Le Prince’s family thought he was killed by Thomas Edison. But he's also a massive red herring, because obviously Thomas Edison wasn't going around murdering people.

What other physical places from the book did you spend time in?

Louis Le Prince had houses in Leeds and he had a workshop, and I would do the wonky stuff of walking from one to the other. I went to the house where he was born, in Metz, France, and I went to the places in Leeds and Paris where some of those film attempts were shot. There's a whole thing about his family waiting for him at Battery Park, looking for him when he never turned up, so I would go down there and walk around.

What about the Morris-Jumel Mansion in Washington Heights, where his family had settled at the time of his disappearance?

I literally just ran out of time on my trip to New York.

The Edison archive at Rutgers that you mentioned—it’s a whole entire research center, and they have something like five-million documents, much of it digitized. Was that hard to navigate?

The website's actually pretty good, where you can kind of search a name, search a date, search a subject, and it'll bring up most things. I was really lucky because Paul Israel, who oversees that project, I wrote to him quite early saying, Do you have any pointers? And he wrote back saying, There's a bunch of stuff about that period that we've digitized but not made public yet, but here's a WeTransfer link to some gigantic PDF files. So he had done a little bit of curation work for me.

I assume you didn’t make it through all five million documents.

The stuff he sent me, I made it through every page. Everything else was a case of almost, like, reverse-engineering court cases where Dickson and Edison had claimed, We did this on this date. And so it was about verifying, OK, where actually were you on that day? What does your notebook say on that day?

How does the Edison archive at Rutgers compare to the Louis Le Prince collection in Leeds, which I imagine is not quite as vast?

It isn't at all. There's the National Science and Media Museum. They have one of his cameras on display, or a camera projector, and they have a plaque about him and a bunch of stuff in the back—other cameras, projectors, reels, some paperwork, but it's mostly clippings or after-the-fact stuff. There's another place called the Leeds Industrial Museum at Armley Mills, and they have records of the Whitley Company, which is essentially Louis Le Prince's in-laws’s company. They have his father-in-law's correspondence with him. And then there's a whole bunch of stuff that was donated to Leeds University by the Le Prince family—pages from his notebooks where he did sketches, early drafts of patents, correspondence, that kind of stuff. And then Lizzie Le Prince, who was Louis’s widow, she had a kind of unpublished memoir

Where is the memoir located?

The family have copies and they sent me a copy.

What other sorts of materials did his descendants provide?

They had the kind of stuff many families have. Old photographs, old correspondence. By the time I came around to it, most of it they had donated to Leeds University. But there's one branch of the family, the descendants of Louis's brother who now live in Memphis, and they keep the torch up and try and talk about him and get attention back to him.

What did they have in their possession that was unique?

A lot of it was duplicates of what is at Leeds. And then there was a lot of other, kind of seemingly meaningless correspondence. There were other members of the family, like nieces and nephews of Louis’s or Lizzie's or his siblings, who had written memoirs, or their own recollections, where you can gather little details like, okay, that's how Lizzie was at the end of her life.

You had a number of researchers who were able to be in places that you couldn't be in.

This is a bit of a spoiler alert, but there's a whole thing at the end that has to do with financial documents, and a marriage contract, and what someone's financial situation was at the point in time when Louis disappeared. A lovely amateur genealogist in Dijon found all these old papers at a local notary and scanned them in for me, and I was able to read them. There's something also near the end having to do with a body that was pulled out of the Seine after Le Prince disappeared. It was one of those online photographs, like, is this real or whatever? I had a young history student in France who was recommended to me by the French publisher of my previous book, and she traveled back and forth and found not just the photograph, but the ledger that it went in, and the guys who worked on it, and she took copies of these things and got them cleared. And then there was one guy, who wasn't my researcher in any way, called Jacques Pfend. He died shortly before the book came out. He was a film academic, and he had researched every arcane detail of Le Prince's life for decades and was obsessed. Really diligent. And so Jacques and I would have conversations, or he'd send me a PDF or a Dropbox folder with hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pages of arcane stuff. He was so useful and he knew it so inside out, and he wasn't writing a book. He was so generous in sharing what he had found that I entered those three years of research with someone who'd done forty years of backup.

Did he at least get to read an early manuscript before he died?

No. He read pieces, and I hope he kind of got a grasp.

Some of the most esoteric material involved the science and mechanics of those early cameras and motion picture devices, which you delve into in great detail.

I went to film school in the days where, for the first month of your first year, you loaded a camera, unloaded a camera, got a light meter, cut the film. So I had kind of a working understanding. One of the amazing things about this stuff is, the technology is not that different. For me it was more about, how much detail do you need to understand what's going on without having so much detail that it's unbearably boring?

Kind of like the building of the Ferris wheel in THE DEVIL IN THE WHITE CITY.

I’ll happily take that.

In the final pages of the book, you lay out a compelling theory of what happened to Louis Le Prince. You leave a little wiggle room but sound pretty convinced. Do you feel like you solved the case?

I come to every book as someone who's a storyteller. And I try and hold myself to a really rigorous standard. I have cold sweats at night about being found out to be full of shit. But I was hopeful, probably for the first year and a half, that I was going to find a smoking gun. And in a very naive way, it took me a long time to just admit, it's been one hundred forty years—of course there isn't a smoking gun. Once I came to my theory, I batted it back and forth with Jacques. I batted it back and forth with the family. I batted it back and forth with cop friends, lawyer friends. And I feel pretty good about it. I also have that terror that, somehow, because it's been one hundred and forty years, I've got it wrong. But I have yet to test it and find someone who can tell me, oh, you've overlooked this, and the whole house of cards falls apart.