Deborah Cohen on LAST CALL AT THE HOTEL IMPERIAL

Researching the OG foreign-corro supserstars

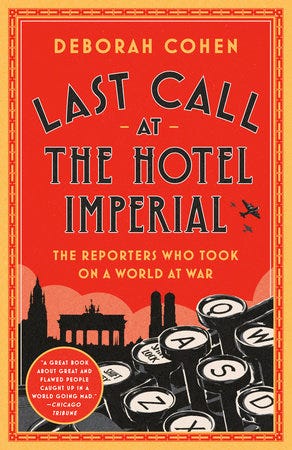

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES! Today we have the brilliant Deborah Cohen, whose latest book, LAST CALL AT THE HOTEL IMPERIAL, is now out in paperback. I devoured this one when it first hit shelves last year, feasting on the swashbuckling foreign-reporting escapades and messy personal lives of journalism legends John Gunther, H. R. Knickerbocker, Vincent Sheean, and Dorothy Thompson. Let’s begin by having Deborah tell you more about them…

It's a book about a group of young American reporters in the early twenties and thirties, who are fed up with the United States and go to make their names in Europe and Asia. And they become, in a sense, the people who set the mold on what a dashing foreign correspondent should be. They interview everyone who is anyone, from Mussolini to Stalin, Trotsky to Hitler. They end up chasing two stories. One of them is the rise of fascism, where they function basically like Cassandra, warning their fellow Americans of what's going to happen. The second big story is the rise of anti-colonial nationalism, with nationalists fighting against the European empires. And then I guess I would say a third story finds them: the story about the relationship between the individual reporters’ souls and the world events around them. As a consequence of being steeped in all of these world agonies, they end up wondering about the relationship between their own inner life and the events that they're reporting on, and they end up writing some really taboo-breaking books, especially in the form of the modern memoir.

This might sound like an obvious question for a professor of modern European history, but how did you come to this story?

I had written a little piece for The Wall Street Journal on books about parents and children, so I went back and read John Gunther's Death Be Not Proud, which I'd loved as a kid. I realized the Gunther archive is like, eight miles from me. I was curious about him and about readers’ responses to that book, so I went off to the archive.

Where is his archive?

At the University of Chicago. It really was like a Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe thing. Like I pushed on the back of the covered door and there I was. The archive is 250 boxes; 125 boxes are listed online, and then there's another 125 boxes that an archivist, after I'd been sitting there for about three weeks, came out and said, Oh, you know there's another finding aide, right? That more personal archive contains correspondence with people like, you know, Eleanor Roosevelt, every head of state that you could think of, every editor and literary person of any kind of significance.

And this was in…?

2015. I was teaching at the time and it became something of a secret preoccupation, because I wasn't really sure what I was doing with it.

So you're going through Gunther’s archive and you start to get a sense that there's the makings of a book.

I was thinking first of all about writing just about John and Frances Gunther. (Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library.) But then there were the really vivid voices of their friends—not all of their friends, but the people who I ended up writing about. They were the kind of people who, like, jump out of the archive and grab you by the throat. It was clear that so many of them were coming to their ideas about the world in conversation with each other.

In your bibliography, I counted something like five or six dozen archives overall.

Nearly all of them were in person. As the pandemic happened, there were a couple I couldn't get to and people sent me stuff, which was incredibly nice. For historians, going to dozens of archives for a book is totally normal.

And these archives took you from Chicago to…?

To Vienna. To London. To Berlin. Um, to Delhi.

That sounds blissful, globe-trotting around to archives.

Totally blissful. It represents two sabbaticals worth of work, and then summers and other bits I cobbled together. The first one was mostly researching and the second one was mostly writing. And then Covid happened when I was trying to finish the book.

Were there any particularly notable adventures in the archives?

I would say almost every one of them. I was used to working in pretty interesting archives, but these were so amazing because you have these people who were really committed to the idea that private life, the history of private life, has to be preserved. They are themselves working out, over thousands of pages, why it is that they feel the way that they do, and then preserving it, and feeling like it's really important to preserve. So you get these almost Rashomon-like accounts from four different people's perspectives. That's true of the political events, of course—something like the Spanish Civil War, and arguments about the Spanish Civil War. But it's also true of stuff like, you know, marriage. I mean, there are arguments about orgasms, not just between the husband and the wife, but also between, like, other people who know about this entire thing.

Which of the characters ended up being your favorite to sort of go down the rabbit hole with?

I have two favorites actually. One is Vincent Sheean, who I think is brilliant. In a sense, Sheean's questions were always my questions too. As a historian, I had always wondered about, what's the relationship between the individual and society? What's the relationship between all those families talking about, you know, the bachelor uncle at the dining room table and how social change actually happens? And Sheean was interested in exactly that. All of his private writing is so—these people just sparkle when you read their stuff. Their personal dilemmas, their political dilemmas, even their writerly dilemmas. I also am, like many people who read her stuff, enamored of Mickey Hahn, the New Yorker writer, who's not one of the main four characters. She was always on the verge of taking a bigger part in the book, but it had to be a group that was all linked together, and Hahn was only linked to two of them.

The story I felt myself being pulled along with the most was the Gunthers’. I felt like Frances Gunther was an honorary member of the central cast.

Yeah. Strictly speaking, she doesn't make her name as a foreign correspondent, so she doesn't fit in as, you know, a ‘world famous foreign correspondent,’ but she's equally important. What was it for you that you found them the most interesting?

Maybe just because their marriage was so complicated? And I feel like you got to know them the most. I feel like I got to know Dorothy Thompson the least of the four. At some point she kind of just goes and hangs out on her farm in Vermont or whatever. I just felt like it was easiest to get pulled into the Gunther story.

I mean, on some level, you're absolutely right. The book really did start as being about the Gunthers, and then I think I felt increasingly like these other lives are also woven together.

The narrative walks this line between these really weighty historical convulsions, like the rise of fascism in Europe, and then the personal lives and romantic and sexual proclivities of the main characters.

What I wanted to be able to show was how they functioned integrally together. You know, oh my god, when they're thinking about Hitler, they're thinking about themselves, or they’re thinking about their parents. When John Gunther's sitting in Spitall in the Austrian backwater interviewing the Hitler relatives, and Hitler's mother says to him, ‘You must be a success’—that's what Gunther's mother said to him, too, and he can't report that without having a kind of flash of recognition. And so the question in the writing was, how to give the reader the sense that this is happening, while keeping enough of the geopolitical story going. There were three things to balance: the journalistic work, the geopolitical story, and the inner-life story.

Some of the subject matter gets pretty dark. Not just like, Nazis, but also the Gunthers’ son dying of brain cancer. Was there any point during the research where you just kind of felt emotionally drained?

One of the heartbreaking things is the parents' letters written to Gunther after the publication of Death Be Not Proud. There's just thousands and thousands of these letters, this catalog of misery. But also, in a way, unexpressed misery. You were the first person who I can tell this to. My minister tells me not to dwell on these things. Those are just utterly wrenching.

What’s something you dug up that had never been published before, as far as you know? The juicier the better.

Do you want a private-life example or do you want more of the political moment?

Private life would be good.

One thing that genuinely took me aback was, the ways in which Frances Gunther actually is trying to conceive of the female orgasm. She doesn't really have the vocabulary. She always talks about it as an ‘org.’ I don't know if it was like, a terminology that they had? The idea that a psychoanalyst is treating both husband and wife, and essentially tells Francis, you’ve gotta lie about not having orgasms because he has to have his. That glimpse of early psychoanalysis in the wild west of psychoanalysis, there's a lot more to say about that, but for me, as a historian of private life, that was pretty surprising.

Plus when you're writing about dead people who left their papers behind, they may not have expected something like that to end up in a major book.

No no, she wanted it to end up in a book. It's the opposite problem. I mean, this is the same thing with the Dorothy Thompson archive. By the time Jimmy Shean is writing his tell-all book about the Thompson-Sinclair Lewis marriage, there's a whole question of like, well, would Dorothy Thompson have wanted her lesbian affair to be in that book? And John Gunther and Sheean, and everyone who knows Thompson, including her sister, say, yeah, it's fine. This is why she saved those papers, and that's why she put them in that archive.

Did you find any things that you thought were too personal for publication?

Yeah, and they're not in the book. Things that felt extreme. Things that involve third parties of complete insignificance. Or things that are ancillary enough to the narrative that they're not important. I would say that the problem, when you have these people who have left a very deliberate archive, the problem is actually something different, which is, to what extent are you falling into the trap that they have left for you? So it's like, Oh, historian, come here, I've got a lot of juicy archives for you! You wanna know something about the private life of Stalin? Well, here it is! You wanna know about what it felt like to be there on the Night of the Long Knives? It's all here for you!

Can you say what you're working on next, if anything?

I would say I'm still speed dating topics.

Well is there any archive that you're just kind of milling around in like you did with the Gunther archive eight years ago?

I haven't found that Pandora's box—yet.

CLICK HERE TO BUY LAST CALL AT THE HOTEL IMPERIAL

MORE SOURCE NOTES: