Sara DiVello on BROADWAY BUTTERFLY

Another juicy Jazz Age murder mystery

Welcome back to SOURCE NOTES. This is a special one, because my guest is Sara DiVello, author of the brand-new historical crime thriller BROADWAY BUTTERFLY, based on the sensational 1923 murder of Roaring Twenties showgirl Dot King. When I say “based on,” I really mean, “so exhaustively researched that it’s essentially a work of nonfiction.” I encountered the Dot King mystery while working on BLOOD & INK, which shares a major character with Sara’s adjacent Jazz Age yarn: the pioneering crime reporter and early Daily News star Julia Harpman. (Who married Westbrook Pegler before he became a famous syndicated columnist and mid-century populist firebrand.) BROADWAY BUTTERFLY also includes cameos from OG tabloid boss Philip Alan Payne, who was Harpman’s editor and close friend, as well as the hero/anti-hero of BLOOD & INK and my favorite of all the characters I researched for the book. Sara and I are very likely the two people on Earth who have spent the most time digging into the lives of these obscure, larger-than-life journalists from a century ago. We had lots to talk about…

The origin of BROADWAY BUTTERFLY was a chance visit to the remnants of an old Gilded Age estate.

I'm from Philadelphia. I was home for Thanksgiving, having leftover turkey sandwiches and hanging out with my aunts and uncles and cousins. My uncle Ed started saying that he and my uncle David, back in the sixties, after school let out, would sneak over to the old Stotesbury Estate and sneak cigarettes and beer. My aunt lives in a very normal, modest suburb where everything is a split-level ranch circa 1950, and he was saying, you know, it was this castle.

Your antenna went up.

I'm like, what castle? And he is like, yeah, there used to be this incredible estate and there are still ruins. So all eleven of us ended up piling into three cars and caravanned over. And there, between the Subarus and the tulip beds, are indeed the ruins of a great estate. Headless statues of Diana. Fifty-foot-tall pillars in somebody's backyard. The remnants of a fountain. It was so bizarre and so cognitively dissonant. So I went down the rabbit hole on Whitemarsh Hall: one-hundred-forty-seven rooms, three floors above ground, three floors below ground, its own gymnasium, its own radio station, its own movie theater at a time when movies were just developing, a staff of seventy full-time gardeners just to maintain the grounds. I learned everything there was to learn about this building, but at the end of the day, I was like, well, I'm fascinated, but I’m not going to write the history of a castle.

When was this?

This was 2013. I went back to the novel I was already 50,000 words into, but I couldn't stop thinking about it. I could feel there was a story there, or hoped there was. And then in February 2014, in this 1953 book that was something like, “Scandalous Philadelphia,” I found a one-line reference to, in 1923, the Stotesburys—who still are a very big Philadelphia name—found themselves in a very uncomfortable position when Mr. Stotesbury, who was a founding partner of J.P. Morgan, found himself publicly humiliated because his son-in-law—who was also a millionaire and the CEO of the Philadelphia Rubber Company—was one of two primary suspects in the murder of his mistress, who of course was half his age, blonde, and a Manhattan gal about town.

That was the moment you knew you had a story.

The hair on the back of my neck stood up.

Why did you decide to do this as a novel instead of nonfiction?

I worked on this for nine years, like almost a decade of my life, and that entire time, I was writing it telling myself that this was nonfiction, that this was true crime, and I wrote it that way. I was excruciatingly, obsessively careful with all of my facts and details. But after nine exhaustive years, I knew I wasn't going to be able to get certain conversations, like interrogation room conversations, conversations between Julia and Westbrook in the privacy of their Upper West Side apartment, conversations between Frances Stotesbury and her husband. I had to fill in the dialogue that I couldn't get, and there are also two scenes in the book that I had to fill in, based on research that led me to believe exactly what I thought happened in those two scenes. So I decided just to call it fiction, even though part of me felt like, well, I'm almost cheating myself—why the heck did I spend nine years of my life in the bowels of the New York Public Library if I could have just stayed home and imagined it all? But I know that is not the case, because my research is excruciating, exacting, and obsessive.

Give me an overview.

I amassed over seventeen-hundred pieces of research. I got a Newspapers.com subscription, Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, Find a Grave, all of those things. The Library of Congress online archives. The Milstein Microform Room in the New York Public Library. That was a big one, because of when I started this, the New York Daily News archives were not online. I had to, you know, open the drawer, get out the roll, and feed it through. And because microfilm is not searchable, you have to go through every single page.

I was also going through all the other newspapers that were covering the story heavily—The New York Tribune, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Philadelphia Inquirer. I applied for and was granted a research pass to the Morgan Library and Museum. They have boxes of Stotesbury stuff, because he was a founding partner of J.P. Morgan, so they have extensive collections. I spent time in the University of Pennsylvania rare books collection, which is the Kislak Center. And the Columbia University rare books collection—they have Ferdinand Pecora’s papers.

Pecora was the prosecutor?

Yeah. They have an an oral testimony of his life, like hundreds and hundreds of pages transcribed, which is really cool. And then, the secretary to the New York Police Department's commissioner's was a guy named J.C. Hackett, who was a very suspicious and super racist dude, but he had written a tell-all memoir in, I think it was 1932. And allegedly, the Stotesburys bought the entire print run and burned it. There's no copies left of that book. Hackett moved to Canada and republished the book, which is eighty pages. It's more of a pamphlet. There's only two copies left in the entire world, and UPenn has one of them, which I found in WorldCat. When I called them to see if they could scan it to PDF for me, they weren't even aware that it was in their holdings. They hadn't protected it, so the paper had disintegrated. They had to call in an antiquities paper expert.

That’s incredible. What were the main sources you used to develop Dot King?

All of Julia's articles, obviously, and then all the articles by other reporters. The head of the homicide department, Arthur Carey, wrote a memoir and he devoted a whole chapter to her. The secretary to the medical examiner also wrote a memoir and he also devoted a whole chapter to her. Also, J.C. Hackett's eighty-page rant, and I interviewed a lot of professors.

Like, academics familiar with the Dot King case?

There was only one who was familiar with the case, a professor at Boston College who specializes in how police and police violence were portrayed in the media at the turn of the century. Everyone else was speaking more generally about women at that time, working women at that time, Irish women, whatever.

Were there any characters that were particularly challenging because there wasn't a ton in the historical record?

Ella.

Dot King’s maid?

Yeah.

Why was she challenging?

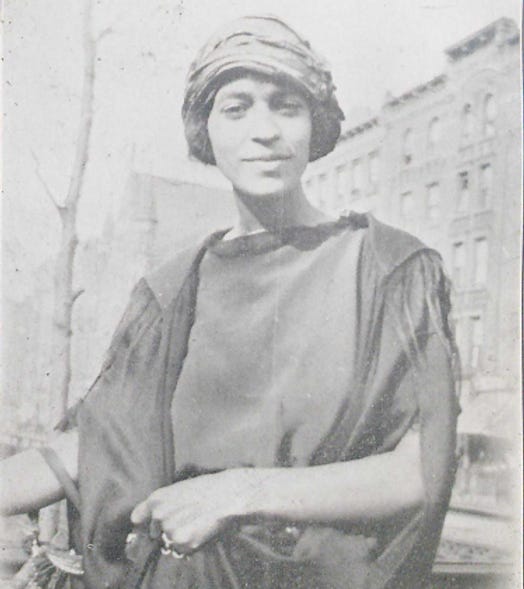

As I'm sure you know, women are harder to track than men. Women at that time didn't even have their own passports. It was harder to track marriage records, birth records, passports, travel, anything, because sometimes they don’t even use the woman's name. Sometimes it'll say, you know, Mrs. Joe Pompeo. So, A) women were harder to track than men, and then, B) Ella was a Black woman, so there were even less records about her, due to the extensive racism at the time. She appeared in the papers, she was in all of the memoirs. I spent a lot of time trying to find her birth certificate. I never found it. I was able to find her marriage certificate, and I was able to find two photos of her after six or seven years of searching. It felt like striking gold, hitting the lottery.

The character I’m most familiar with, obviously, is Julia Harpman. [Pictured below with Phil Payne, left, and Westbrook Pegler.]

I recognized scenes in the book that were straight from the historical record, like when she arrived in New York and tried out for the Daily News. How much of the book is comprised of actual real-life anecdotes like that?

Everything is from historical research. The only things that I made up are based on information from which I was able to strongly hypothesize.

Some of the dialogue comes from newspaper articles or other primary records.

I used as many direct quotes as I possibly could and only filled in what I had to.

So a scene like Ella in the interrogation room—you found references to that and just had to create the dialogue?

Carey put it in his memoir! He literally was like, I had her make a list of all her Black male friends because this was a, quote-unquote, “colored crime.”

Did he describe details like Ella crying?

I put in the crying, because I thought, I would cry! She was twenty-three. I mean, I would be scared to go into a police station now, and I have a college degree and I'm white and 45. A twenty-three-year-old Black woman all by herself—it must have been terrifying.

What are some of the historical topics that you needed to gain expertise in, and what types of scholars did you consult?

I interviewed professors of women’s and gender studies, human sexuality studies at the turn of the century. I interviewed a professor who specializes in 1920s political campaigns. The professor at Boston College, who studies how police interrogation and brutality were portrayed in the media at the turn of the century. I researched what life was like for immigrants. The presidential election and Jazz Age politics. A professor who studied Ferdinand Pecora. A professor who studied Westbrook Pegler. A professor of forensics. The head of the Southern Jewish Historical Society, to help me understand what life was like for a Jewish girl [Julia Harpman] from Nashville in 1923. A professor, who happens to be Black, who really helped me think about the careful, sensitive, full-bodied crafting of a Black character. I also worked with a professor of English literature, who also happens to be Black—I hired her as a sensitivity reader, and then my publisher also hired a sensitivity reader. [You can find the names of all these folks in the acknowledgments.] I wanted to get this right, because these are real people, and they deserve to be honored and encompassed in the wholeness and complexity of their humanity.

Dot King’s murder went unsolved. How did you approach the book’s ending? You could have decided to solve it.

While I was very tempted to tie it up with a neat and tidy bow, because I like closure, as we all do, that would not have honored the story. And my intention in writing this was to honor the truth of the story and these incredible real life people. To do that, I had to adhere to the truth. And the truth is, the crime is not solved. Booklist said that I’d given readers all they need to reach their own conclusion, and that was exactly what I wanted to do.

»CLICK HERE TO BUY A SIGNED COPY OF BROADWAY BUTTERFLY

MORE SOURCE NOTES:

Damien Lewis on AGENT JOSEPHINE

Lisa Belkin on GENEALOGY OF A MURDER

I just finished Broadway Butterfly and Julia's interpretation of how the murder was committed kept me awake most of the night. It certainly made sense to me!

Ironically, I had read Blood and Ink about two months ago. It is in my finished pile of books. I'm going to have to scan it to see if I recognize some of the names.

Both books left a lot of questions unanswered about the unsolved murders. Both books were very enjoyable and head scratchers. Only three people know - the victim, the murderer, and God. Nobody is talking.

You should look into the unsolved murder of Hollywood director William Desmond Taylor. Silent film director. Lots of theories about his death.